A Brief History of Comics

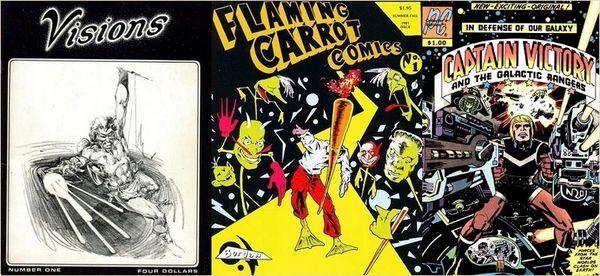

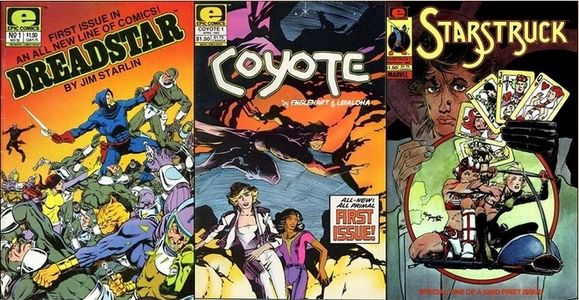

There are a LOT of books on the history of comics. Above are covers of some of the books that I've read and think are quite good. If you want a quick summary with some samples of comics across the history of the art form and don't want to read an entire book about it, you can get a quick summary here.

If you have the time, do a search on Amazon (or the internet in general) on "History of Comics". You can dig into lots of information and lots of different viewpoints about this history of this fascinating topic.

Comics Through the "Ages"

Comics fans and historians split the history of comics into "ages", which are sequential periods of time that each have a shared feel reflective of the general trends in comics during the years that the "age" spans.

At ComicSpectrum we will also call out some key sub-divisions within ages (and sometimes spanning multiple ages). Each has its own unique characteristics that are worth calling out and are worth examining and understanding.

Ultimately, it's useful to break up and understand the common sub-divisions in the history of comics for collecting purposes. Many people like to specialize on collecting from one or multiple ages, or even concentrating on collecting within some of the specialized sub-divisions, like EC or Underground comics .

PLATINUM AGE (PRE-1938)

The Platinum Age applies to all comics that came out before the 1st appearance of Superman in 1938 and is a very specialized area of comics collecting. The number of people collecting these comics is very small and less is known about them than comics from the Golden Age forward, but they undeniably laid the foundation that modern comics were built upon. Popular character from the pre-super-hero days include R.F. Outcault's The Yellow Kid, George McManus' Bringing Up Father (with Jiggs & Maggie), and Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse.

Golden Age (1938-1956)

The Golden Age of comics is considered by most fans and comics scholars to have started with the first appearance of Superman in Action Comics #1 (June 1938) and ran through 1956. Action Comics #1 changed the landscape of comic book from that point all they way to today. Batman soon followed, debuting in Detective Comics #27 (May 1939) and then a host of other super-heroes who would ultimately form a team, The Justice Society of America, in All-Star Comics #3 (Winter 1940). Super-Heroes became very popular and soon dominated the majority of the titles that were being produced. DC Comics (known as National in the Golden Age) is often thought of first when people think of the Golden Age because of iconic characters like Batman and Superman.

Timely Comics (that would eventually go on to become Atlas and finally Marvel Comics) burst onto the scene not long after the debut of Superman and Batman, offering up Marvel Comics #1 in October 1939, debuting the iconic characters of the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner. Captain America joined them in March 1941 and the Golden Age had another strong stable of super-heroes for the young fans to buy.

The third major contender in the Golden Age super-hero market was Fawcett Comics. Their most iconic super-hero was Captain Marvel, debuting in WHIZ Comics #2 (Feb 1940). Fawcett created a number of other heroes over the years, but none had the endurance of Captain Marvel and the "Marvel Family". Their adventures dominated the comics at Fawcett, they would guest star in a number of other comics and even introduce new characters to the Fawcett fans. There were certainly other publishers during the Golden Age, dozens, but the 3 spotlighted here created the most enduring super-hero characters.

By the early 1950s, with the exception of Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman, the Golden Age of Super-Heroes was over. DC's "Big 3" would keep the lights on until the super-hero resurgence that became known as the Silver Age.

When it comes to back issues from this time period, as you might expect, they're getting older and tougher to find. Action Comics #1 for example: it's estimated that only 50-100 copies of this book still exist and with that rarity comes value. In 2011 a copy of Action Comics #1 in really nice condition sold for over $2 million dollars! If you're looking to buy or collect back issues from this time period, just understand what a challenge it could be, especially in higher grades.

EC Era (1949-1955)

EC Comics started in 1944 publishing Pictures Stories from the Bible, at that point in time EC stood for "Educational Comics". After World War II the popularity of superheroes started to decline and comics about crime, horror, science fiction, and war started to gain in popularity. In 1949/1950 EC started publishing comics to meet that demand and their titles soon became top sellers with more mature stories that did not talk down to the readers and top notch creative talent. At this point EC sttod for "Entertaining Comics".

As these types of comics became more popular, so too did the controversy surrounding comics contributing to juvenile delinquency, which came to a head with the publication of Seduction of the Innocent and Senate hearings on juvenile delinquency in 1954. Although no correlation between crime/horror comics and juvenile delinquency was ever proven, the comic book industry took a hit. As a result of the hearings the Comics Code Authority (aka CCA) was created, ostensibly to prevent the spread of juvenile delinquency due to "objectionable" comics material.

In reality, many authorities on comics history believe the CCA was created by mainstream publishers of the day with an explicit intent to put EC Comics out of business, essentially eliminating a competitor who was outselling their tamer books handily. EC tried to re-tool with a focus on more acceptable topics like doctors and newspaper reporters (which they called their "New Direction"). This was unsuccessful and after trying a few "picto Fiction" books, essentially illustrated stories, EC was reduced to their humor comic Mad, which was changed to the magazine format we are familiar with today, mostly because as a magazine it was exempt from the CCA.

ATOMIC AGE (1949-1956)

Super-heroes were on the outs by the end of the 1940s. Most DC Golden Age super-heroes ceased publication by 1951 (with the exception of Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman, known as DC's "Big 3"). Fawcett's Marvel Family titles were gone by 1954. Over at Timely Captain America held out until Sept 1954 and the Sub-Mariner ceased publication in Oct 1955. While the super-heroes were waning in popularity, other genres were gaining dominance on the comic stands. This era is characterized by a popularity of Western, Romance, War, Sci-Fi, and Horror comics, mirroring genres that were also popular on radio, TV, and movies. It was in this environment that EC Comics thrived (see above), but EC was not the only publisher putting out comics in this transitional period in between the Golden and Silver Ages of super-heroes, there were a lot of publishers who had a start in the Golden Age who continued publishing diverse genres in the 1950s. But when all is said and done, the Atomic Age is really an overlay onto the end of the Golden Age and a shorthand that collectors will often use when referring to non-super-hero comics of the 1950s.

SILVER AGE (1956-1970)

After the demise of EC and the creation of the Comics Code, super-heroes started to make their comeback in what is known as the Silver Age. As with the Golden Age, the Silver Age began with DC Comics and was heralded by the re-imagination of a number of Golden Age DC super-heroes with new science-based origins. The reintroduction of The Flash in Showcase #4 (Sep/Oct 1956) is generally acknowledged as the beginning of the Silver Age. Green Lantern was reintroduced in Showcase #22 (Sep/Oct 1959). These heroes banded together to form the Justice League of America in The Brave and the Bold #28 (Feb/Mar 1960). DC continued these revitalizations with Hawkman in The Brave and the Bold #34 (Feb/Mar 1961) and the Atom in Showcase #34 (Sep/Oct 1961) both of whom would later go on to join the Justice League of America.

The success of the super-hero relaunch at DC caused Marvel Comics Publisher Martin Goodman to ask Stan Lee to create a super-hero team for Marvel. What Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created was Fantastic Four #1 (Nov 1961) and with that, the Silver Age was well and truly off and running. The Fantastic Four was quickly followed by super-heroes like Spider-Man in Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug/Sep 1962), Ant-Man in Tales to Astonish #35 (Sep 1962), the Incredible Hulk #1 (May 1962), Thor in Journey into Mystery #83 (Aug 1962), Iron Man in Tales of Suspense #39 (Mar 1963), The Wasp in Tales to Astonish #44 (June 1963) and two team books: X-Men #1 (Sep 1963), as well as a closer analog to DC's Justice League, The Avengers #1 (Sep 1963).

The Silver Age of comics is one of the most, if not the most, popular age with collectors today because of the amount of iconic characters created or relaunched during this time. Collecting comics from this era provides a fan with great history and stories about where the characters came from who are still popular today and making a huge name for themselves in movies, TV, and video games.

Bronze Age (1970-1985)

Although there really isn't a single agreed upon comic that marks the beginning of the Bronze Age like there is with the Silver Age, many consider the Bronze Age to begin around 1970 and run through 1985. As comic books started to tackle current topics like drug use and war that the Comics Code Authority previously tried to keep out of comics, comics began to be a little more serious, this shift of focus in mainstream super-hero comics is a key feature of the Bronze Age. For example, in 1971 Marvel Comics published a Spider-Man story that dealt with drug use. Although the Comics Code did not allow the use of the CCA stamp on the book, Marvel put it out anyway. In the same timeframe, Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams were dealing with similar topics in Green Lantern. 3 months after the CCA-less issues of Amazing Spider-Man, Green Arrow's sidekick Speedy was actually revealed to be a drug addict in a similarly CCA-seal-free issue. The publishers were no longer letting the CCA totally dictate their content, when the situation warranted it, they would forgo CCA approval. Around that same time, minority characters like Luke Cage and John Stewart were introduced bringing much needed diversity to the pages of comics.

Collecting and purchasing back issues from this time period brings you a truly diverse amount of material. We started to see a wide variety of genres creeping onto the stands from Marvel & DC to augment the staple of the industry, super-heroes. With titles like Conan the Barbarian, House of Mystery, and Master of Kung-Fu, to name but a few. The Bronze Age widened the variety of genres in comics to include something for everyone, in surprisingly sophisticated stories, for the first time in over 15 years.

The perfect end point of the Bronze Age is embodied in 1985's massive DC Comics crossover event "Crisis on Infinite Earths" that wrapped up and simplified 50 years of DC Comics continuity by doing away with the concept of DC's multiverse, a somewhat convoluted concept (for people who were not hard-core comics fans) involving multiple parallel earths where all the DC Comics stories ever published could exist all on their own different versions of earth; Earth One for Silver Age stories, Earth Two for Golden Age stories, Earth-S for Captain Marvel family, etc.

Underground Era (1967-1982)

Underground Comix emerged in the 1960s as part of the counterculture of free love, drug use, and rock music (sex & drugs & rock'n'roll). They used comix instead of comics to differentiate from the mainstream and also to indicate the presence of more adult content. These comix began in the early 1960s but didn't gain a strong popularity until 1967. 1968 marked an early milestone with the publication of Robert Crumb's Zap Comix, which featured the debut of Underground Comix icon "Mr. Natural", as well as Crumb's iconic Keep on Truckin' image. These comix were regularly sold in 'Head Shops', stores that specialized in selling drug paraphernalia.

Characters like Mr. Natural, Wonder Warthog, and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers captured the imagination of a generation of free-spirited young people, along with stories featuring non-specific characters who used drugs, spent time in conflict with or evading police, and mocking the establishment and political figures of the time. The irreverence and humor hit a chord with fans and over time these comix started to attract more and more creators who had something to say that didn't fit in the confines of corporate-owned comic books featuring super-heroes. As the 1970s progressed, the lines between "Underground" and "Independent" (or 'Indie') comics began to blur, as the subject matter moved away from primarily illegal drug use and sex to include topics like feminism, environmentalism, gay liberation, politics, and autobiography (like Harvey Pekar's self-published American Splendor). Once direct sale comic book shops began to appear in greater numbers in the late 1970s, there was less reason for these comics (which could not be sold on comics spinner racks targeted at children) to only be sold in Head Shops, and they moved into the comics shops along with the other comics presented as an alternative to the mainstream super-heroes.

Copper Age (1980-1994)

There are many definitions for the Copper Age with a wide range of debate as to the starting & ending years. It seems to exist more as an attempt to continue the naming of ages after metals than anything else. The DC Wikia suggests this age ran from 1980-1985 and ended when Crisis on Infinite Earths wiped away the multiverse concept from the DC Universe. Choosing 1980 as the beginning of this age is likely related to the launch of New Teen Titans in that year. Pulling the beginning of the Copper Age back to 1980 causes the problem of either overlapping it with the Bronze Age OR suggesting the Bronze Age ended in 1980, which would give it a span of only 10 years, slightly short for an "age" when compared to the Golden and Silver Ages. The DC definition that has it running for only 6 years is not only very short, it also takes the concluding event (Crisis on Infinite Earths) that is the perfect capstone to mark the ending of the Bronze Age and moves it into the Copper Age. The overlap with the Bronze age and overall short span of years of the DC definition would lead me to dismiss it as the definitive definition, but perhaps it works if you are only looking at DC Comics and ignoring all other comics.

Other sites attribute a date range for the Copper Age of 1984 through 1991 or 1992, suggesting that Marvel's Secret Wars crossover was the start and the end was heralded either by Jim Lee's debut on X-Men in 1991 or the mass exodus of Marvel artists in 1992 that led to the founding of Image Comics.

Several other sites (that all seem primarily set up to sell comics, particularly those from the "Copper Age") list the end of the Age as 1994, but give no explanation since they are stores, not sites interested in documenting or explaining terms. 1994 is an interesting choice as the end of the age since 1994 was a very tumultuous year in comics, marking the collapse of the speculator market.

So, a number of conflicting and overlapping definitions for a Copper Age of comics, with issues ranging from an overlap with the end of the Bronze Age to lengths that seems too short to define an age and an overall lack of a unified theme for the age, relying instead on external market forces and events to define the beginnings/endings. Combining the multiple concepts and making

Indie Era: Birth of the Indies (1978-1992)

"Indie" comics is kind of a loaded term. In many cases the definition today is just "Not Marvel or DC", but that is not a definition that can extend back through history since many publishers like Archie, Fawcett, EC, Dell, Gold Key and many other non-Marvel/DC companies have had a long history and presence on the racks alongside the super-hero books. That said, by the late 70s super-heroes had been the predominant force in comics for a while. As alternates to this super-hero dominance began presenting themselves to readers once again, it was certainly a noticeable change for fans and the concept of "Indie comics" started getting some play among comic book collectors of the day, many of whom had been predominantly buying from the "Big 2" for many years. Having a number of other choices in comics that were not perceived as being aimed directly at younger readers, as was the case with Archie & Gold Key, was something that made the maturing base of comic fans sit up and take notice. Typical fans were now in their late teens, 20s, or even older, as opposed to a much younger predominant demographic in the 1960s and earlier.

Late 1977 and early 1978 brought some key properties to light that would enjoy long runs and become iconic independent comics success stories. Cerebus the Aardvark debuted in December 1977 and ran for 300 issues, the exact number that Dave Sim said he'd do early on when he created the series. Elfquest debuted in Fantasy Quarterly #1 in Spring of 1978 and would go on to be featured in more than 100 issues from many publishers and translated into many languages. Also in 1978, we got the 1st publication from Eclipse Comics, the graphic novel "Sabre" that would go on to be a comic series in 1982.

1979 brought us The Flaming Carrot, with an origin of "Having read 5,000 comics in a single sitting to win a bet, this poor man suffered brain damage and appeared directly thereafter as — the Flaming Carrot!" The Carrot first appeared in Visions #1, finally starring in his own on-shot comic in 1981. 1981 also brought us an independent series from Jack Kirby, the "King of Comics". It is somewhat appropriate that a man who was a key creator in the Golden Age of Comics, co-creating Captain America in 1940 with Joe Simon, and who heralded the arrival of the Silver Age by co-creating the majority of the Marvel Universe with Stan Lee, was there at the birth of Indie comics with his creation Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers in November 1981.

There was an explosion of independent publishing from that point on, with a number of publishers coming into existence and putting out a tremendous variety of comics throughout the 1980s. Some were around for a limited time, others are still publishing comics today.

Additionally, the birth of independent comics would not have been the same without the inadvertent assistance received from Marvel Comics via their Epic imprint in 1982. Seeing the growing popularity of companies like Eclipse and Pacific, Marvel spun up a line of very different comics featuring a creative alternative to their standard super-hero fare and offering a large degree of creative freedom and also allowing creators to retain ownership of their properties. There were a lot of fans who would not have otherwise tried out these very different (from standard super-heroes) comics, but since they were from an imprint of Marvel, try them they did. Many fans had their horizons expanded and they would ultimately find themselves open to trying comics from a number of other independent publishers.

In November 1988 a number of independent comic book writer and artists got together and drafted a Creator's Bill of Rights, designed to give creators proper credit for their characters and stories, profit sharing, fairer contracts, return of original art, among other things. Comics were maturing due to the work of many hard working and imaginative creators who wanted fair treatment and compensation for the compensations they were making to the industry. This movement would go on to make lasting changes and paved the way for a more creator-friendly comics industry.

Key Indie Publishers of 1978-1992

Aardvark-Vanaheim (1977-present) publishing it's flagship title Cerebus as well as initiating titles such as Neil The Horse (Feb 1983), Journey (Mar 1983), normalman (Jan 1984), and Puma Blues (Jul 1986).

WaRP Graphics (1977-2010) an acronym for Wendy and Richard Pini, was founded primarily as a mechanism to publish the Pini's Elfquest (Apr 1978) after its debut in Fantasy Quarterly. They would later publish non-Elfquest series including Colleen Doran's A Distant Soil (Dec 1983) and MythAdventrues (Mar 1984) based on the successful fantasy novel series by Robert Lynn Asprin.

Eclipse Comics (1978-1993) who published Sabre as a Graphic Novel in 1978 and expanded their publishing lineup with such notables as Destroyer Duck (May 1982) which featured the 1st appearance of Sergio Aragonés' creation Groo the Wanderer, Ms. Tree (Feb 1983), DNAgents (Mar 1983), Somerset Holmes (Sep 1983), Aztec Ace (Mar 1984), Doc Stearn...Mr. Monster (Jan 1985), Miracleman (Aug 1985) a highly acclaimed reworking of the 1950s British character Marvelman (himself a thinly veiled reworking of Fawcett's Captain Marvel), Scout (Sep 1985), and Airboy (Jul 1986) another revival of a character from the 1950's.

Pacific Comics (1981-1984) publishing Jack Kirby's Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers (Nov 1981), Mike Grell's Starslayer (Feb 1982); Pacific Presents (Oct 1982) an anthology that had the 1st appearance of Dave Stevens' Rocketeer, Alien Worlds (Dec 1982); Sergio Aragonés' Groo the Wanderer (Dec 1982) continuing on from his 1st appearance in Destroyer Duck #1, and a comics version of Michael Moorcock's Elric (Apr 1983) beautifully illustrated by Michael Gilbert & P. Craig Russell

Epic Comics (1982-1994) was an imprint of Marvel comics that allowed creators to retain control and ownership of their creations. It spun off from the Epic Illustrated magazine into it's own line, sold only via the direct market, starting with Jim Starlin's Dreadstar in 1982 and soon expanded to contain many more popular titles including Elaine Lee's Starstruck, Steve Englehart's Coyote, and Carl Potts' Alien Legion, to name only a few. The Epic imprint was responsible for making quite a few Marvel fans expand their tastes in comics beyond the super-hero genre and may have done as much to foster the growth of independent books, by providing a large number of willing fans eager for more and different comics, as any other single factor in the early 1980s. In time, the Epic line skewed back towards the costumed characters and ended up being a place for Marvel to publish more mature versions of standard Marvel super-hero stories, but the key role it played in the early days of independent and creator-owned comics paved the way for many companies that followed who allowed creators a publishing home while retaining ownership of their intellectual property.

Fantagraphics (1982-present) started in 1976 and published the eminent magazine about comics, The Comics Journal ("a quality publication for the serious comics fan") starting in Jan 1977. It was not until the classic Love & Rockets (Sep 1982) that Fantagraphics started publishing original comics content. This was followed by the sci-fi series Dalgoda (Aug 1984) "Fantagraphics 1st direct sales mass-marketed comic" and Peter Bagge's Neat Stuff (Jul 1985)

Comico: The Comic Company (1982-1987) like Vortex, started with an anthology series Primer (Oct 1982) which debuted Matt Wagner's character Grendel in issue #2. Several series debuted in 1983, the one that was successful was Grendel (Mar 1983) who would star in a total of 4 series from Comico before the company went out of business. Other notable series from Comico included Matt Wagner's Mage: The Hero Discovered (May 1984), Bill Willingham's Elementals (Nov 1984) and Robotech: The Macross Saga (Dec 1984)

Vortex Comics (1982-1994) started with the self-titled anthology series Vortex (Nov 1982) and followed that in 1984 with new titles Stig's Inferno (early 1984) and Mister X (Jun 1984). Other notable series were Matt Howarth's Those Annoying Post Bros. (Jan 1985) and Chester Brown's Yummy Fur (Dec 1986). It went out of business as a result of the direct market crash in 1994.

First Comics (1983-1991) started out with the Warp (Mar 1983) based on the 1971 original sci-fi play Warp! produced in Chicago that moved to Broadway in 1973. This was soon followed by E-Man (Apr 1983) a revival of the super-hero who first appeared in a Charlton Comics series in 1973 with original artist Joe Staton still on board. Works original to First included Mike Grell's Jon Sable, Freelance (Jun 1983), Mike Baron's Badger (Jul 1983), Howard Chaykin's masterful sci-fi/political satire American Flagg! (Oct 1983), and John Ostrander & Tim Truman's Grimjack (Aug 1984). First also continued to pick up creator-owned series from other publishers: Mike Grell's Starslayer (from Pacific with #7, Aug 1983), Steve Rude's Nexus (from Capital with #7, Apr 1985), and Jim Starlin's Dreadstar (from Marvel's Epic imprint with #27, Nov 1986). First also published a number of mini series featuring characters from Michael Moorcock's Eternal Champion mythos, including Corum (2 series), Elric (5 series), and Hawkmoon (4 series). First "came back from the dead" in 2015, in a merger with Devil's Due, calling themselves 1First Comics LLC, and the combined publisher Devil's Due / 1First Comics (that's a mouthful!).

Continuity Comics (1984-1994) was started by popular comics artist Neal Adams in 1984 with the publication of his series Zero Patrol (Nov 1984), It would go on to publish titles such as Hybrids, Megalith, Ms. Mystic (1st published by Pacific and resumed by Continuity in 1987) and many more. It went out of business as a result of the direct market crash in 1994.

Mirage Studios (1984-2009) is best known as the birthplace of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (May 1984). Mirage published a number of other titles, mostly spin-offs from the Turtles for years until they sold their assets to Viacom in 2009, while still retaining rights to publish up to 18 TMNT comics per year, if they so desire.

Renegade Press (1984-1988) spun off from Aardvark-Vanaheim when publisher Deni Loubert divorced Dave Sim. A-V kept Cerebus but the other titles, most notably Flaming Carrot Comics (with #6), Neil the Horse (with #11), Ms. Tree (with #19), and normalman (with #9) all followed Loubert to Renegade. Renegade's first original works were Gene Day's Black Zeppelin (Apr 1985) and Valentino (Apr 1985). They went on to publish a number of other series, including Wordsmith (Aug 1986) and Eternity Smith (Sep 1986) but were plagued by low sales and put out their last comics in 1988.

Antarctic Press (1985-present) started with Mangazine (Aug 1985) and pioneered a style that Antarctic refers to as 'American Manga', which are really just American comics that are heavily influenced by Japanese manga art style and some story themes, though produced in standard American comic book format and reading left to right. This is very different from Japanese manga translated into English and published for an American audience, which would be coming in a few years. Antarctic's longest running title was Ninja High School (Jan 1987) that would ultimately run 195 issues in addition to a number of spin-offs and specials. It's interesting to note that NHS switched to Eternity Comics (an imprint of Malibu) for issues #5-39. Mangazine would return for volume 2 (Jan 1989) and help get Antarctic back on a regular publishing schedule.

NOW Comics (1985-1994) was founded by Tony Caputo and published primarily licensed comics material like Fright Night, The Green Hornet, Married...With Children, Speed Racer, The Terminator, Twilight Zone. It went out of business as a result of the direct market crash in 1994.

Apple Comics (1986-1994) spun off from WaRP Graphics and was most notable for publishing Don Lomax's Vietnam Journal war comics, a number of other titles such as Blood of Dracula, The Miracle Squad, and Vox, Fish Police (which they picked up from Comico with #18), as well as FantaSCI and MythAdventures which they inherited from WaRP.

Malibu Comics (1986-1997) also known as Malibu Graphics, was a key player during the "black & white boom" of the late 1980's publishing a number of titles that received a lot of critical acclaim in comics fandom with solid storytelling and art. Malibu used their main Malibu logo for a number of titles, including super-heroes like The Protectors and a number of characters spun out from that team (The Ferret, Gravestone, Man of War; aka Genesis Universe titles) as well as the popular spy spoof The Trouble With Girls and licensed titles such as Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Over their life they also published comics under a number of other imprints including Aircel and Eternity (both of which ceased publication as a result of the direct market crash in 1994).

Aircel Comics (1985-1994) - Aircel started as an independent publisher and was bought by Malibu's Eternity imprint in 1988. Aircel started out publishing the popular American-manga style comics Elflord, Dragonring, & Samurai and would expand to many other series including the original Walking Dead zombie series (long before the Robert Kirkman series of the same name) and a number of other black & white comics. Aircel's biggest claim to fame was in publishing the original comic series Men In Black that would spawn a highly successful movie trilogy starring Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones. By 1989 the Aircel imprint was chiefly used for publishing Malibu's 'erotic' comics series.

Eternity Comics (1986-1994) - Eternity started as an independent publisher financed by the same person who financed Malibu. It was merged with Malibu as a publishing imprint in April 1987. Popular Eternity titles included Ex-Mutants, an adaption of the manga Captain Harlock (which was published until Eternity realized they didn't actually have the rights to the character), and a very successful series of Robotech comics published as Robotech II: The Sentinels. After the buyout by Malibu, a number of popular titles were published under the Eternity logo including Dinosaurs for Hire and Scimidar.

Dark Horse Comics (1986-present)

Dark horse was founded with the concept of creating an ideal atmosphere for creators. Their first publication was an anthology comic, Dark Horse Presents, that ultimately ran for 157 issues, ending in 2000, but was revived in 2011 (and again in 2014). Within a year of that first issue of Dark Horse Presents, Dark Horse had expanded its line to over 10 titles. Over the years they would being translations of Manga to American audiences, present many creator owned series (like Frank Miller's Sin City) and also run many licensed series like Star Wars, Terminator, Aliens, and Predator. One of the most successful publishers of its era, Dark Horse still operates today and is one of the Top 5 publishers in comics.

VIZ Comics (1987-present)

Viz started out publishing Japanese Manga in comic book format for the American market. These conformed to the standard left to right reading format and size of US comics, so the art had to be "flipped" from the Japanese right to left format. After the first few years, they abandoned the comic book format and switch to the Japanese tankobon 'graphic novel' formal that were thicker and could be shelved at bookstores, which ultimately led to a manga 'boom' in the US in the 2000s as many more people were exposed to and bought the volumes in bookstores. Viz continues to publish translations of Japanese manga to this day, occasionally breaking into the top of the sales charts.

Innovation Publishing (1988-1994)

Innovation was one of the earliest comic companies to specialize in 'licensed' comics, tie-ins to popular media properties. This helped them, at one point, to rank #4 in comic book market share. They had series based on TV shows like Beauty and the Beast, Dark Shadows, Lost in Space, and Quantum Leap; novels by authors like Anne Rice and Piers Anthony; and movies like Nightmare on Elm Street, Child's Play and Psycho. They also had a number of original series and put out some really great comics, but were a casualty of the 1994 Direct Market crash.

Tundra Publishing (1990-1993)

Tundra was founded by Kevin Eastman to provide a venue for progressive creator-owned comics by well-regarded creators in a format with high production values, including nice paper stock and square binding. Notable works include Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, Dave McKean's Cages, Steve Bissette's Taboo, and Rick Vietch's Maximortal. Unfortunately short-lived, they managed to put out a lot of high quality comics during their short lifespan.

Dark Age (1986-1998)

Called by a few the Iron Age, to follow the metallic progression of ages, many more people think of it as the Dark Age. As comics began to skew towards an older readership as the Bronze Age progressed, comics continued to get edgier and grittier. With historic stories like Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Watchmen (1986), and Batman: The Killing Joke (1988), darker more adult-oriented themes abounded. Characters being maimed or killed and the inclusion of dystopian political concepts into the stories became fairly common.

During this time frame comics and the heroes changed quite a bit, a common term describing them at the time was "grim & gritty". In the 1990's most of DC's main heroes died, were seriously injured, or retired and came back again: Superman died (1993), Batman's back was broken (1993) and he turned the mantle of the Bat over to another even more violent individual and Green Lantern went crazy and killed most of the Green Lantern Corps (1994). There were bright spots among the gloom, but they were overshadowed by the storylines with the injuries, mayhem and death that were getting the most attention (and the most sales).

Colorful costumes were covered up with leather jackets, punching bad guys was replaced with shooting them, the general demeanor of the books was dark. External market conditions in the comics industry were beginning to mirror the dark and bleak worlds the stories themselves were set in.

DIRECT MARKET CRASH (1994)

The health of the comics industry took a hit and almost collapsed when the speculator bubble burst in 1994. At least 19 publishers went out of business, as well as two thirds of comics specialty stores in the US closing up their shops.

A lot of smaller comics publishers that we didn't take the time to detail in the "Birth of the Indies" write-up didn't make it past the crash of 1994. Axis Comics, Blackball Comics, Comic Zone Productions, Continüm Comics, Dagger Comics, Fantagor Press, Majestic Entertainment, Ominous Press, Revolutionary Comics, and Triumphant all ceased publication in 1994.

Generate excitement

What caused the crash? There were a lot of #1 issues, variant covers & gimmick books published in the early 1990's. There was an influx of buyers from outside the traditional comics market who were buying up multiple copies of issues thinking they'd be worth a fortune one day. Publishers were printing and selling over a million copies of some issues. Speculators were buying comics as though they were stocks, looking to get rich. The publishers fed this frenzy by putting out limited "gold" covers, hologram covers, embossed covers, etc. The gimmicks were selling very well, but were not rare and were not investment-grade blue-chip stocks. Ultimately, the speculator boom resulted in a bust that almost killed the direct comics market when the speculators realized that the comics they were hoarding were never going to be worth hundreds or thousands of dollars and they all stopped buying comics as "investments" and the market for these hundreds of thousands of "investment comics" vanished almost overnight.

What was the flaw here? Basic supply and demand. If there are a million of something and buyers are preserving them with an eye towards reselling them later they're not exactly rare. When the speculators realized that their "investments" were not appreciating they left the market. They were not buying comics to read. Once the perceived value was gone, the speculative buyers were gone right along with it. Comic shops that were used to ordering massive quantities of books to sell to the speculators (and they were buying them on a non-returnable basis) found themselves sitting on huge reserves of unsold comics that tied up their cash reserves. Thousands of comic book shops went out of business and there was a contraction in both sales and the number of collectors as a lot of people moved out of the hobby.

1995, 1996, and 1997 continued to be very rough years for comics. In December 1994 Marvel Comics acquired Heroes World DistributionCo. in an attempt to set themselves up to distribute their own comics, which would reduce the market share of other distributors by one third. The change took place in July 1995 and had a ripple effect that almost wiped out the comics direct market. In 1996 Diamond Comics Distributors acquired Capital City Distribution, and in 1997 Heroes World went out of business with Marvel Comics returning to Diamond Distributors, making Diamond the 'only game in town' supplying the comic book direct market. Comics had weathered the storm but it had been a rough couple of years.

MODERN AGE (1998-PRESENT)

Something had to change and fortunately it did. In 1997 DC revitalized the Justice League franchise with a new take titled simply 'JLA' and written by superstar writer Grant Morrison. At the end of 1998 Marvel revitalized their line with the creation of the Marvel Knights imprint pulling in Kevin Smith to write Daredevil (with art by Joe Quesada) and Christopher Priest's reinvention on Black Panther for a new generation of comics readers. The industry was pulling out of the mid-1990s tailspin and entering the Modern Age.

This continued in 2000 with Marvel's launch of their "Ultimate Universe", re-imaginings of key properties driven by creator Brian Michael Bendis, that were not burdened with years of continuity. Marvel's Ultimate Universe provided a useful alternate to the main Marvel Universe but itself ultimately became burdened with over a decade of its own continuity and outlived its usefulness. After 15 years the line ended with Marvel's 2015 Secret Wars event, with a few of the more popular characters surviving to be merged into the main Marvel Universe.

Another key feature of the Modern Age is a prevalence of creators shaping the main super-hero universes who feel that they must leave a mark on each series they take over, making it feel like it is theirs. When a new team comes on board they often toss out everything that was done by the last creative team, sometimes this works better than others, depending on how a creator's new take is received by fans. This led into another facet of the Modern Age, downplaying years of continuity. There is typically a desire for the characters to behave consistently with how they have behaved in the past (though this is sometimes thrown out the window if a creator has a story to tell that entails a complete personality overhaul for a character) but the need to hold every single event that ever occurred as canon that can handcuff the creators from telling the story they want to tell has been discarded. The common credo is 'tell a good story' and let the rest work itself out.

INDIE ERA: RISE OF THE INDIES (1992-2004)

The defining event in the rise of independent comics was the mass exodus of top-selling Marvel artists who left in 1992 to create their own company, Image Comics. The early sales success of Image led to a boom in sales of comics but a lot of this boom was due to the comics speculator market, people who were not necessarily comics readers but who were buying comics in large quantities with an eye towards them becoming valuable for later resale at a profit. Unfortunately, as these comics sold in the millions, there was no way for demand to outpace the supply once the speculators were removed from the equation. There just were not that many fans out there. Once the direct market crash occurred as a result of the speculator bubble bursting a lot of indie companies (and comics shops) went out of business.

The publishers that kept on going post-crash learned that ultimately it was the stories and characters that won out over the flash and carnival-like atmosphere of the early years of the rise of the indies.

Generate excitement

The key publishers (along with a few of their notable series) that came onto the scene during the period from 1992-2004 were:

Image Comics (1992-present) was founded when Erik Larsen, Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld, Todd McFarlane, Whilce Portacio, Mark Silvestri, and Jim Valentino all left Marvel Comics to create their own company where they could own their creations instead of doing work for hire for a corporation. Each of the core creators created their own studio within Image with autonomous editorial control (with the exception of Portacio, who withdrew during the early days of Image's formation to deal with an illness in his family).

- Larsen created Highbrow Entertainment and started out with Savage Dragon.

- Lee created WildStorm Productions and started out with WildC.A.T.s

- Liefeld created Extreme Studios and started out with Youngblood.

- McFarlane created Todd McFarlane Productions and started out with Spawn.

- Silvestri created Top Cow Productions and started out with The Darkness.

- Valentino created ShadowLine and started out with Shadowhawk.

More to come... this page is still under construction

Copyright © 2018 ComicSpectrum - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy